There is, as the doctor always says in countless medical gags, good news, and bad news.

Let’s start with the good news. In general terms, we are all living longer than our parents and grandparents, and our children are predicted to live for even more years than we will.

That’s the overwhelming conclusion drawn by the mammoth and ongoing Global Burden of Disease (GBC) study, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Gates Ventures and carried out by a range of institutions for the World Health Organisation. (Since 2019 study has been tracking 286 causes of death, 369 diseases and injuries, and 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories.)

But the bad news, delivered in the latest analysis carried out for the GBD, is that frighteningly large numbers of us can expect to live many of those “extra” years in the grip of dementia.

That’s the conclusion of a new study co-authored by hundreds of researchers from around the world, including the UAE and Saudi Arabia, published in January’s edition of the journal The Lancet Public Health.

Dementia is an umbrella term for a group of symptoms, including problems with memory, mood, thinking, language, perception or behaviour, which often start out mildly and gradually get worse.

Often the first sign is disrupted short-term memory — people start to forget things that have happened recently and begin repeating themselves.

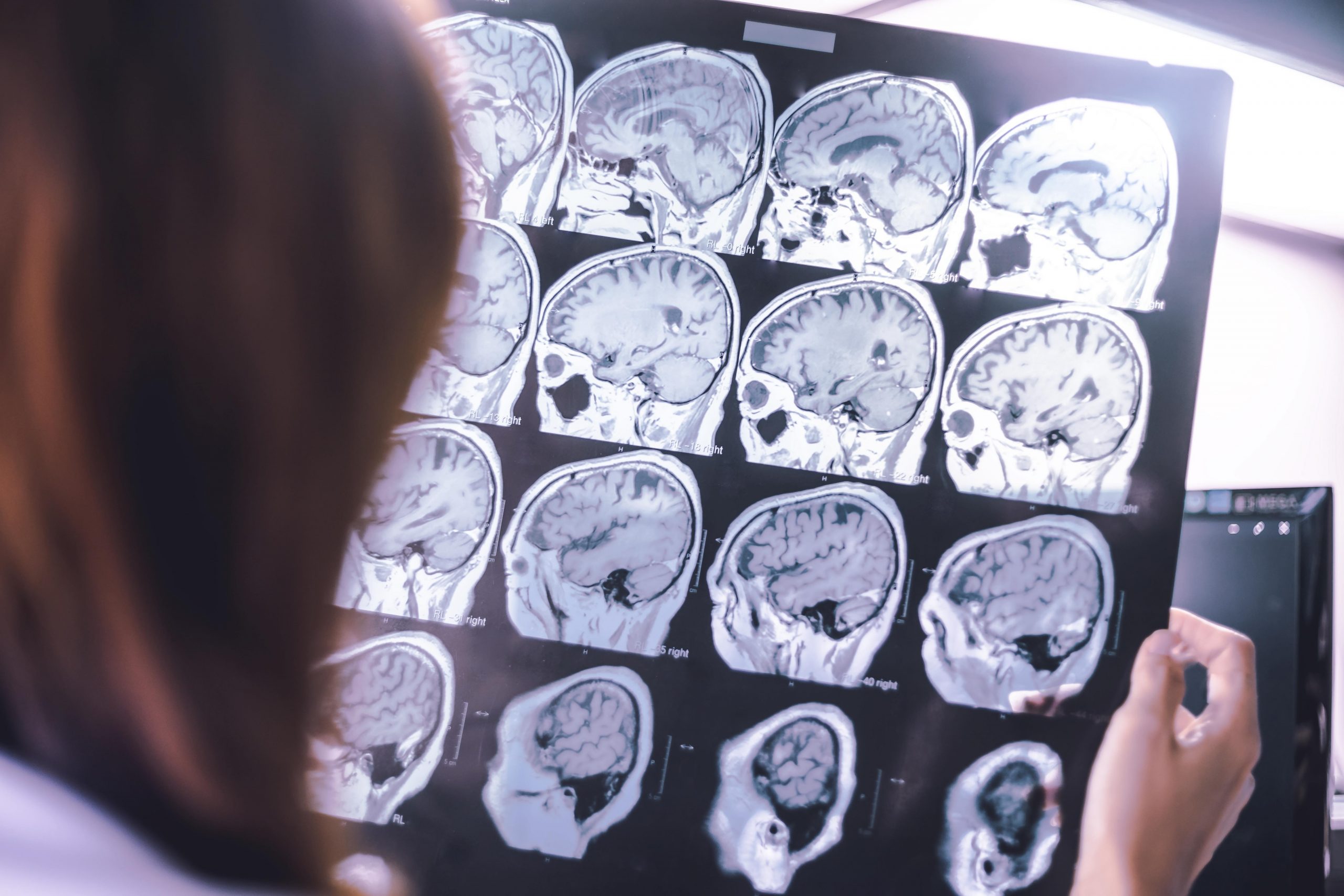

The two most common types of dementia are Alzheimer’s disease, in which the connections between nerve cells in the brain are destroyed, and vascular dementia, in which blocked blood vessels deprive the brain of sufficient oxygen, causing brain cells to die.

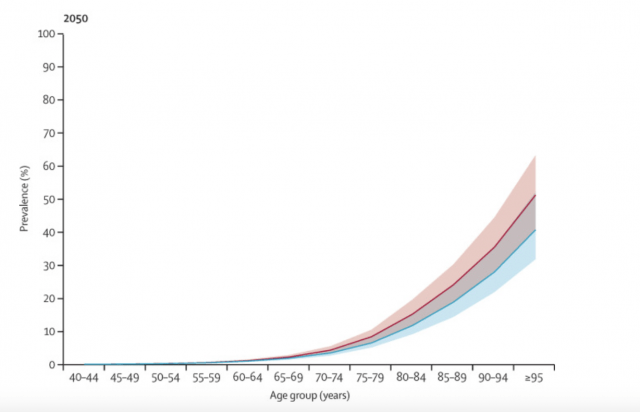

Shockingly, the GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators predict that in the next three decades the number of cases of dementia worldwide will almost triple, from 57.3 million in 2019 to over 152 million by 2050 — an increase of 166 percent.

Ironically, the growing problem of dementia, which threatens to overwhelm healthcare systems around the world, is in part a by-product of success: we are living longer because of reductions in poverty, and improvements in healthcare, nutrition and education.

By those measures, the Gulf states are doing better than most. Take the UAE, where the average life expectancy for girls born in 1990 was 73 years, and for boys just over 70.

By 2017 those figures had jumped to 76.9 and 71.7 years respectively, and it is now predicted that a girl born in the UAE in 2100 can expect to live until she’s 82.4 years old, with boys not far behind, at just over 77 years.

There’s even more to celebrate in Saudi Arabia, where women saw their life expectancy jump almost six years between 1990 and 2017, from 73.6 to 79.4 years, with men’s increasing from 70.3 to 75.3 over the same period.

And by 2100, new-born Saudi girls will be able to look forward to an average lifespan of 84.7 years, with boys living on average until they are 80.6 years old.

The extremely bad news, however, is that dementia threatens to overshadow the final years of life for many of those children. Throughout the six states of the GCC as a whole, in 2019 there was a total of 137,000 cases of dementia. By 2050, however, it’s predicted that the number will have increased to a staggering 1.52 million — an astonishing rise of over 1,000 per cent – among the largest increases globally, the study found.

By far the biggest increase, up by almost 2,000 percent, is predicted for Qatar, based on the number of cases jumping from a mere 4,200 in 2019 to over 85,000 in 2050.

But the UAE, with a predicted surge from 11,711 cases to over 221,000 — an increase of 1,795 per cent — isn’t far behind, and the health systems of the other four GCC states also face testing times ahead.

In Bahrain, the number of people with dementia is expected to soar from 5,126 to 60,650 (an increase of 1,084 percent). Oman’s caseload will jump from 4,200 to 124,893 (up 943 percent), Saudi Arabia’s from 85,735 to 855,760 (898 percent), and Kuwait’s from 18,000 to 171,121 (850 percent).

Part of the problem is a mathematical one. With all things being equal, as the size of a population increases, the proportion of a population suffering from any disease will remain roughly the same, but inevitably the absolute numbers will increase.

Take the UAE. In 2019 it had a population of about 9.7 million. A decade earlier it was only 7.9 million. Today, it is already thought to be in excess of 10 million and there is every sign that it will continue growing. Dubai’s 2040 Urban Master Plan, unveiled in 2020, envisages an increase in population of six million for that emirate alone over the next 20 years. By some estimates by 2050 the population of the UAE as a whole could be over 13 million.

In addition to causing untold distress to sufferers and their loved ones, these dramatic increases in the number of cases of dementia threaten to overwhelm health systems and, as a result, will likely see the costs of health and social-care insurance rocket, for individuals and companies alike.

Unsurprisingly, the authors conclude that their research “underscores the need for public health planning efforts and policy to address the needs of this group,” and that country-level predictions should be used “to inform national planning efforts and decisions”.

There is, they say, no single silver bullet. Instead, “multifaceted approaches, including scaling up interventions to address modifiable risk factors and investing in research on biological mechanisms, will be key in addressing the expected increases in the number of individuals affected by dementia”.

But heading off the threat is not just the responsibility of governments. There is much we can all do as individuals to improve our chances of living long lives not blighted by dementia.

The clue is in that phrase, “modifiable risk factors”.

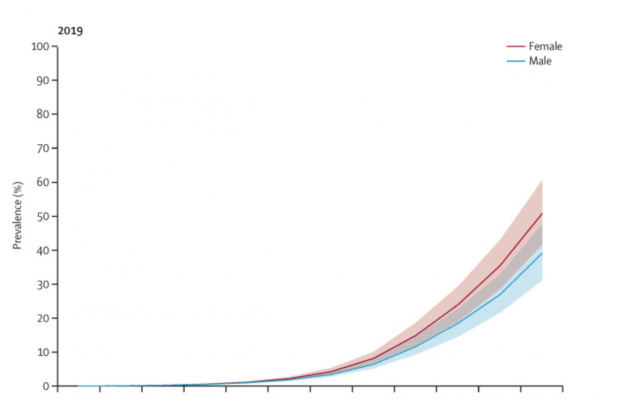

There’s not much anyone can do about the main risk factor — old age — but dementia is far from being an inevitable part of aging. A review of research on the subject published in the journal Behavioural Neurology in 2019 found that the prevalence of dementia in Arab countries ranged from 1.1 to 2.3 percent among people aged 50 years and older, and between 13.5 and 18.5 percent among those aged 80 or more.

In other words, all being equal, four out of every five people in the Arab world can expect to escape dementia.

But all is not equal: age is merely the starting point and in the wealthy Gulf states other risk factors disproportionately increase the chance of an unhappy ending.

To some extent, dementia is an equal-opportunities disease. Although poverty and low education standards have been linked to its prevalence in societies, so too have diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors — all products of plenty, and major issues in the wealthy Gulf states.

A study by Saudi and Dutch researchers published in the journal Obesity Reviews in 2019 concluded that “obesity has increased to an epidemic level in the Gulf States”. The problem is that the Gulf nations share “an obesogenic environment, with a rapid nutritional transition from traditional healthy foods and a high level of physical activity to large quantities of unhealthy energy‐dense foods combined with a sedentary lifestyle and minimal physical activity”.

In other words, after generations of physical adaptation to conditions of hard work, harsh environments and limited diets, the Arabs of the Gulf were not genetically prepared for the multiple luxuries and sedentary lifestyles that the oil boom delivered — and all within living memory.

Levels of overweight (measured by a Body Mass Index of equal to or greater than 25) and obesity (a BMI of 30 or more) “have been increasing significantly during the last four decades”, with increases “particularly dramatic in … Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates”.

In Saudi Arabia, according to the World Health Organisation, the proportion of overweight adults increased from 38.1 percent in 1975 to 69.7 percent in 2016. Over the same period in the UAE the rise was from 45.1 percent to 67.8 percent.

A study carried out in Lebanon, published in 2018 in Preventive Medicine Reports, identified uncontrolled hypertension – high blood pressure — as “the sole significant risk factor that exacerbated the odds of developing dementia”.

In related research, a study carried out in 2016 among elderly Saudis attending an outpatient clinic found that diabetics “were significantly more likely to have cognitive impairment than those who were not diabetic”.

While it would be wrong to suggest that dementia is a choice, as with many things in life ultimately our fate is, to a large extent, in our own hands. If you want to know what to do to reduce your chance of suffering from dementia, you could do worse than follow the guidance published in 2020 by a special commission set up by The Lancet.

After an exhaustive review of all published research on the subject, the commission identified 12 “potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia”: inadequate education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, low social contact, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, and air pollution.

Of course, many of these factors require a lifetime of careful management, such as prioritizing education for all children, controlling midlife systolic blood pressure at 130 mm Hg or lower, stopping (or, better still, never starting) smoking, avoiding living in areas with high levels of air pollution, using hearing aids if necessary (poor hearing and lack of social contact is thought to impair cognitive abilities), and generally “keeping cognitively, physically, and socially active in midlife and later life”.

That means “sustained exercise in midlife, and possibly later life”, which “protects from dementia … through decreasing obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk”.

The authors know that, for many people, “behaviour change is difficult”. Somehow the short-term lure of crashing on the sofa in front of the TV with a pile of snacks to hand overshadows the long-term threat of possibly suffering from dementia.

But, they add, “although behaviour change is difficult … individuals have a huge potential to reduce their dementia risk.”

You have been warned. Call a friend, hit the gym, and ditch the fast food.