Dr Shoji Shiba has helped some of the world’s biggest companies and governments — Toyota, India — turn their way of doing business around and come back stronger than ever.

So how did the business theorist and Professor Emeritus of Japan’s University of Tsukuba create his groundbreaking management theories? The same way he realized he could, and should, open his own mind: by looking at art.

Several pivotal works prompted this inner reckoning. One came decades ago, in Washington, DC, when he realized that Edouard Manet’s 1873 painting The Railway – with its steel fence and clouds of steam – is not only about a woman and child, but also the modernization movement happening at the time.

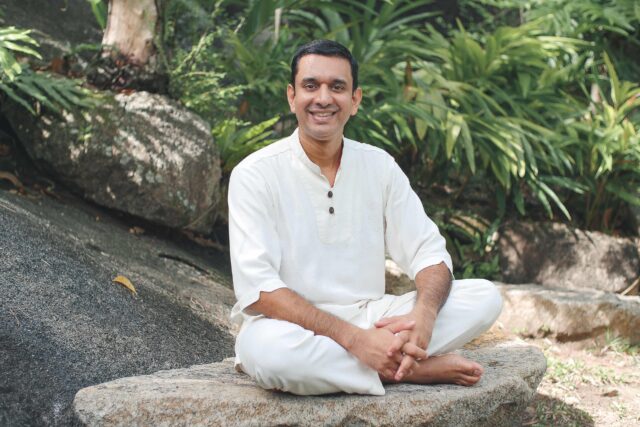

As Dr Shiba told the World Majlis Art For Good session, held as part of Expo 2020’s Tolerance & Inclusivity Week, it was one of several ‘a-ha’ moments.

“Because I was working with statistics, I was dealing with numbers, figures, 1+1,” he said. “But now, once I see images, the images have many, many answers. And all the answers are right. And I realized my mindset was too narrow. I had to transform.”

Dr Shiba was one of several guests at the session who gathered at the Expo’s Terra Auditorium to answer the question: “In what ways can the arts help us look at the world differently?”

Appearing virtually from a remote village in Nepal where he is working on his next project, the Tunisian artist El Seed told those gathered he regularly sees his deeply researched work creating change on a number of fronts. And that happens whether it’s a calligraffiti-style mural in Beirut’s Gemmayzah neighborhood or his half-finished 2017 work The Bridge, which sits on the south side of the North-South Korea demilitarized zone.

“I always see the same process,” he explains. “You come, you propose to people to create a piece of art. Most of the time people are not grateful, first they’re surprised. Because they don’t see in them that what is interesting, what would be worth a big installation, because this is the kind of work that I do. Through the work you make amazing relationships… but beyond that because most of my work is ephemeral, it’s bringing attention to an issue that is important to me. I use this piece of art as a pretext to create social change right after. This is how I use art for me to make the world a better place.”

Sheikha Hala bint Mohammed Al-Khalifa, director general for Culture & Arts at the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities, said El Seed’s project in Al Muharraq — “a very beautiful facade on a very normal apartment building” — sparked positive and lasting change.

“Seed is an incredibly generous personality, so he would take all these people on board and integrate them within the art that he’s creating,” she said. “That building in Muharraq now, all the people who are living in that block, there is this huge sense of pride. You know ‘this artist came, he created this incredible facade, this mural for us’. He brought life into their neighborhood.”

Kirsha Kaechele, artist and curator of Tasmania’s Museum of Old and New Art, talked about a range of community art projects conducted outside the museum — and Australia. One of her projects is The Material Institute, a fashion school for disadvantaged children located in a former mechanics bay in New Orleans. It has been shortlisted for a 2021 Beazley Designs of the Year (Architecture) Award at London’s Design Museum. Another is the 24 Carrots Garden Project, which creates kitchen gardens in disadvantaged areas of Tasmania and New Orleans and uses them to teach young students about every aspect of production and consumption.

“In the physical space, it can manifest as taking a degraded block that no one cares about and putting gardens in and putting art installations in,” she explained. “And through that process, relationships are developed and all this beauty starts to move and emerge in the neighborhood or in the space. I just find that really powerful and to me, I suppose, the art is that transformation.”

Although Kaechele is firmly rooted in the physical world — “ I don’t find technology interesting, and I don’t find technological art particularly interesting,” she told the majlis — these days many projects exist at least partially in the digital realm.

Over in Syria, a project born from the ISIS-destroyed site of Palmyra is serving to link both tangible and intangible heritage as well as bridging gaps between generations.

Dr Patrick Maxime Michel is an archaelogist, senior lecturer and researcher at the University of Lausanne’s Institut d’archéologie et des sciences de l’antiquité.

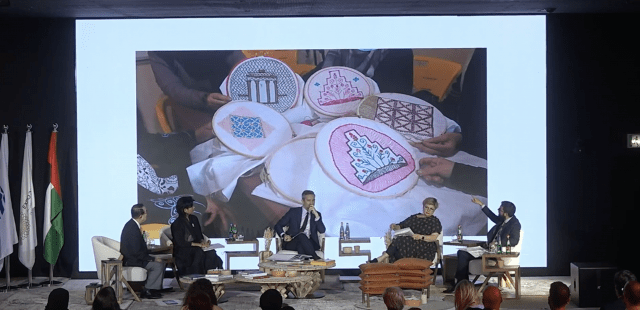

His team created a 3D model of the Palmyra temple that was destroyed and is working with Syrian refugees to “transmit memory” via embroidery bringing both its art and facade alive.

“I didn’t invent this workshop based on embroidery on my own,” explains Dr Michel. “First off, we saw people in the camps producing small models of Palmyra, especially the art. They reproduced using whatever they had in the camps. Small models of the art. Talking to them we said ‘why did you do that? Why was it important for you?’ They said ‘we need something, to link our memories, to transmit it. If I speak to my child about the multicultural history of Palmyra, the beauty of the site, I need to show him something. We lost everything’.”

Realizing they had found their own way to communicate the power of the place, the team settled on embroidery because Palmyra was once a very important stop on the Silk Road. At that time, when a motif was fashionable on a textile, it was incorporated into architecture.

“We took a piece of architecture to speak about the beauty of Palmyra; this is how we link tangible with intangible heritage, and this is how you perform art,” said Dr Michel. “And when people get back to the camp they keep that with them, and they have a way to fix this memory.”

Professor Grazia Tucci, director of the Geomatics for Environment and Conservation of Cultural Heritage laboratory in Italy, headed up the 3D rendering of Michaelangelo’s David that has been a major draw to Italy’s Expo 2020 pavilion.

That project was designed to create the most accurate digital model possible, she explained, but it has also become — as so many public art projects do — about building relationships.

“It was a way to connect people. We discovered a lot of new tools we didn’t know before. They existed before, but we used them in a really creative way. When I talked about digitization, I was not thinking of it just as a product. To build a relationship among people. We have to use this kind of perspective to create a relationship between the digital and the real world.”

Another project in Bahrain was born in Covid, and involved a competition to create public seating areas along the Pearling Path, one of three Unesco World Heritage Sites in the country.

The winners’ “public chairs” will tell the story of the country when they are revealed next year, on National Day.

“Art is such a beautiful language to express and to talk and to share,” said Sheikha Hala. “And if we can inspire or put some spark, then we’ve done it. Whether it’s preserving a World Heritage site or the history of a certain area, this is the true essence.”

• Livehealthy editor Ann Marie McQueen worked on the team that produced the Tolerance & Inclusivity Week’s Art for Good World Majlis.